Every scientist has a story of how they became who they are. Here is mine.

Early Curiosity and First Encounters with Nature

My decision to become a scientist began somewhere between the ages of six and seven. I still remember when a doctor came to my elementary school for medical check-ups and asked if I already knew what I wanted to be when I grew up. My answer was: “A cop!” That was the last time I can remember not wanting to become a scientist.

Never mind that my adult height of only 5 foot 4 would have disqualified me from entering the German police academy — by the time I was seven, I was determined to become a scientist, more precisely a zoologist. You may wonder how this came about, and how I eventually ended up as a marine geomicrobiologist.

I am the only child of my parents, and I grew up in a small German town near Hannover, in the middle of Lower Saxony — at least two and a half hours from the nearest coast. My grandfather, father, and uncle owned a family hardware and lumber store. My mother stayed home when I was little and later returned to work as an industrial clerk when I reached puberty. Nobody in my parents’ families had ever gone to university.

Our house was completed on the same day I was born, giving my parents reason to celebrate two major events — the roofing ceremony and toasting their baby girl — within twenty-four hours. The house was (and still is) surrounded by a large garden. My parents planted trees (a weeping willow, birches, fruit trees) and bushes that grew up alongside me. On the west side of the garden, there was no other house, only a natural area with two fish ponds, wildflower meadows, and more trees. Beyond that stretched agricultural fields. When I looked out the window of my childhood room, I saw nature — not the untouched wilderness of a national park, but enough to attract frogs, kingfishers, herons, ducks, songbirds, birds of prey, mice, rabbits, hedgehogs, martens, deer, and countless insects and spiders.

Above: The natural landscape behind my childhood home — where my curiosity first took root.

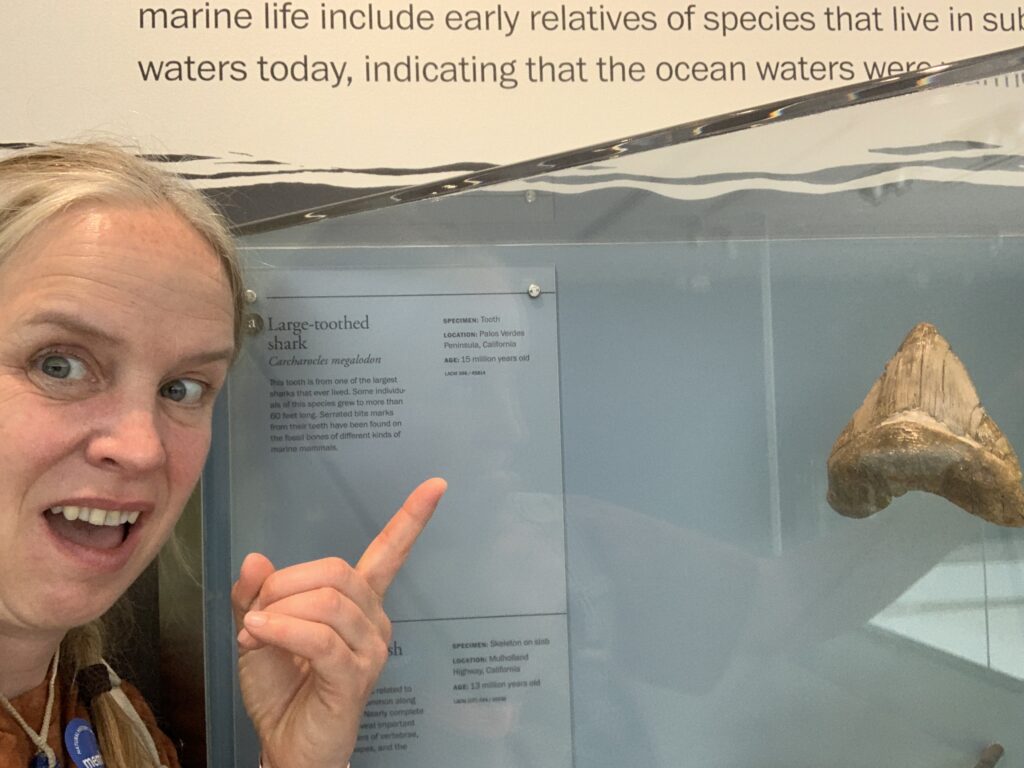

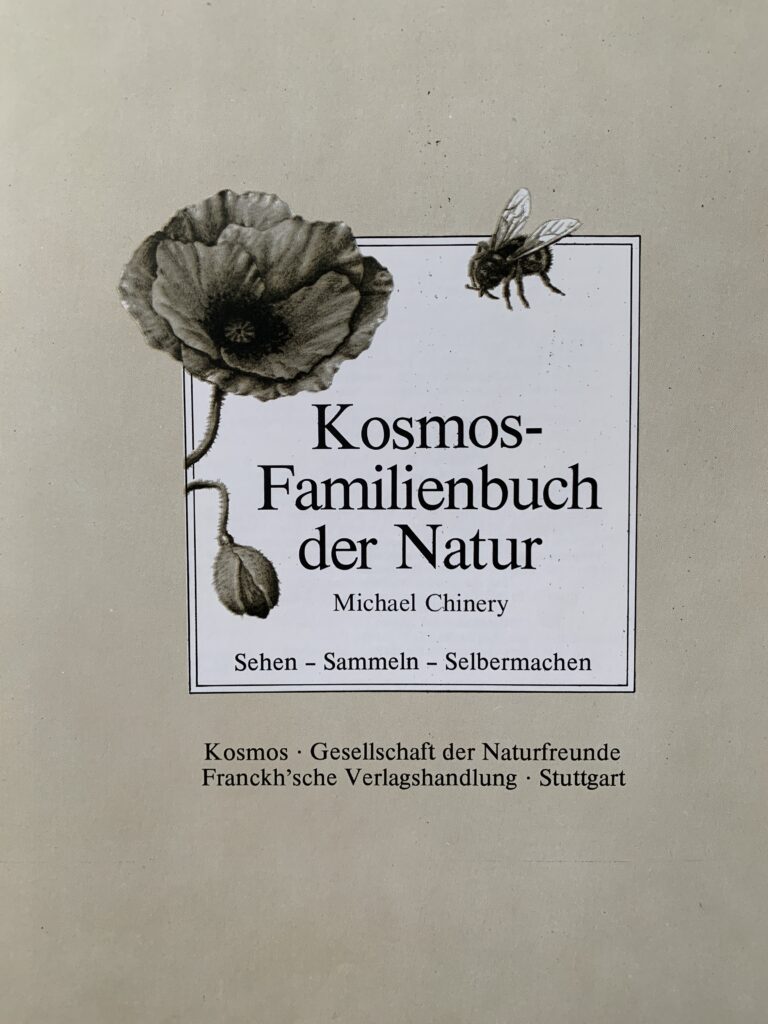

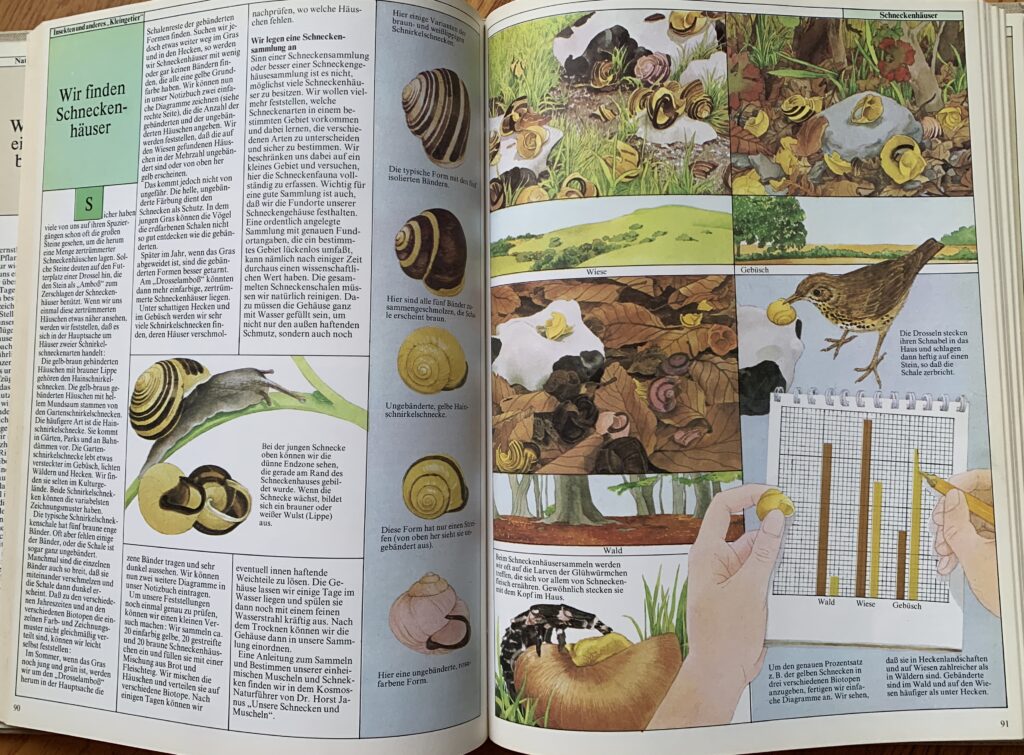

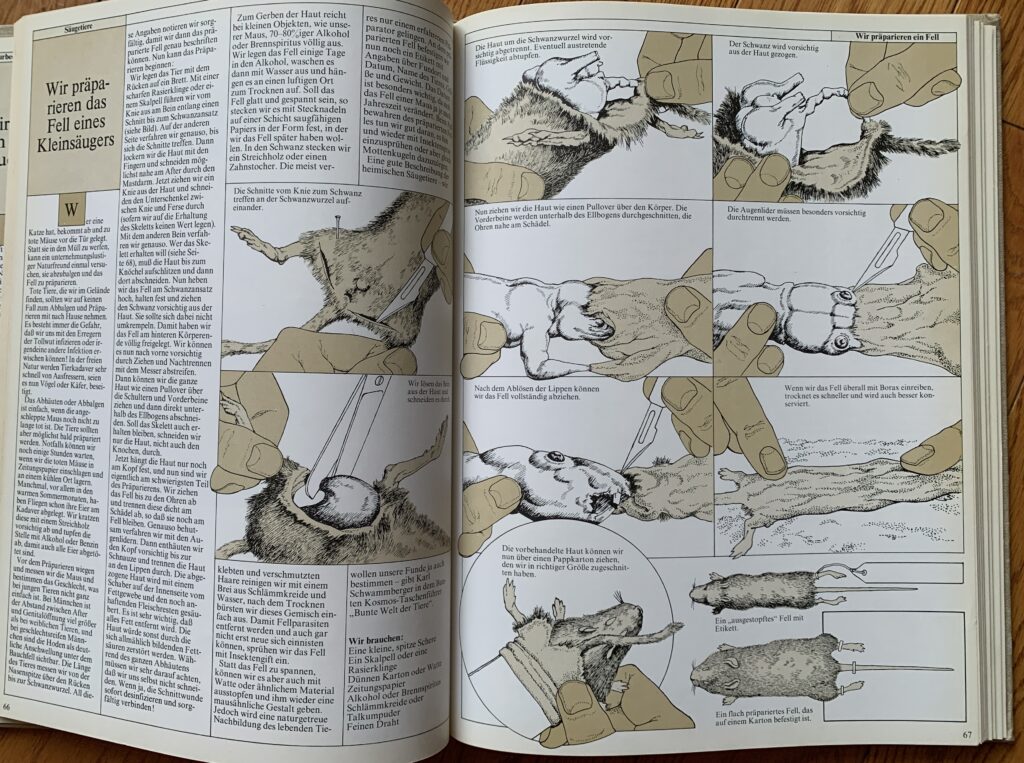

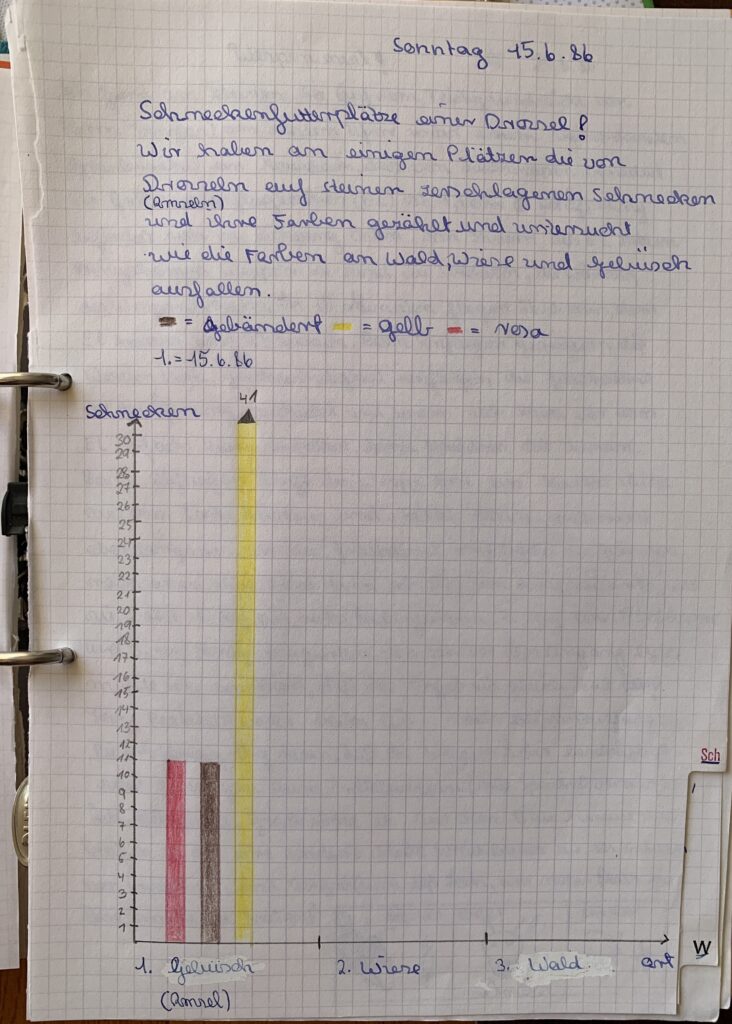

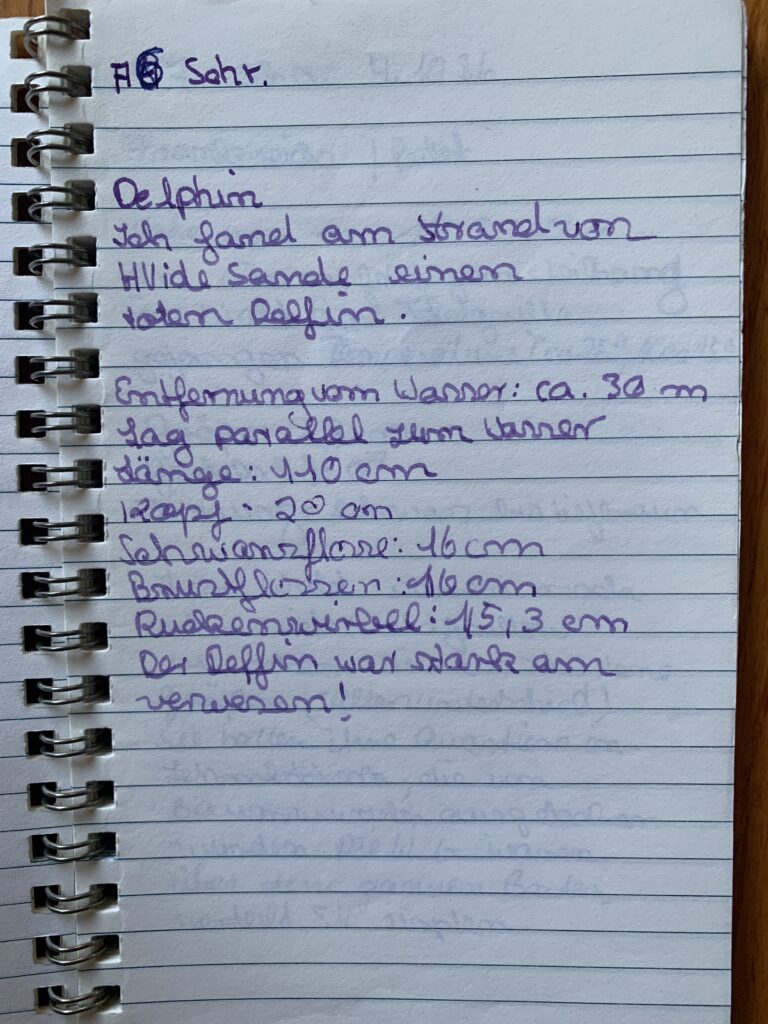

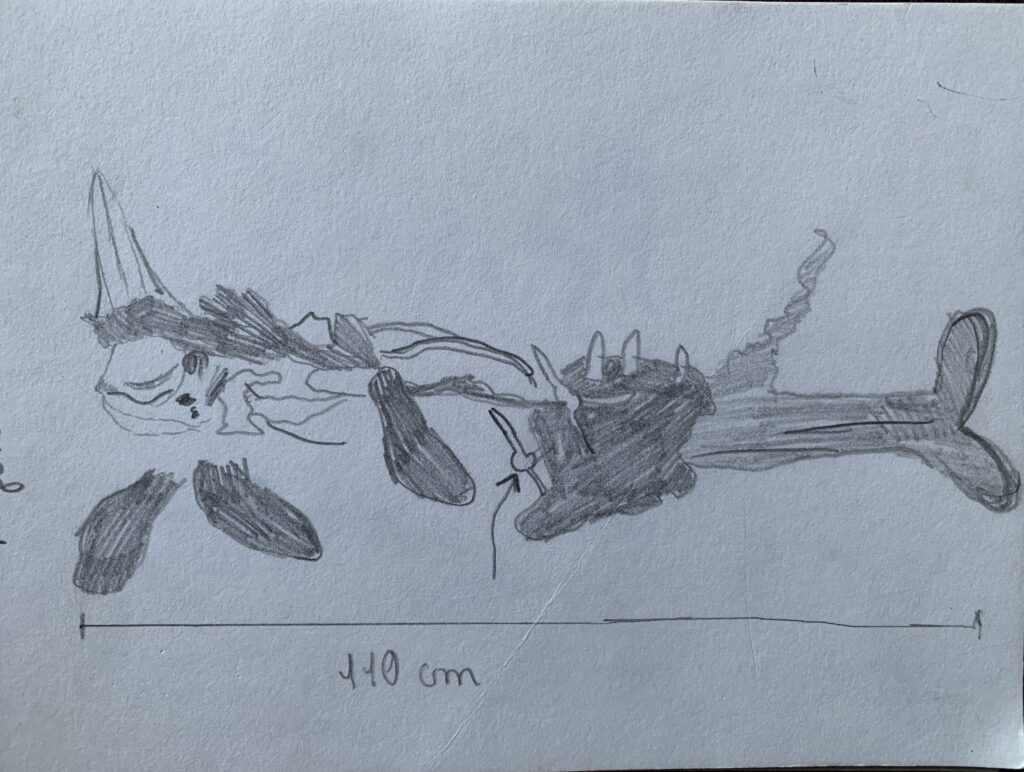

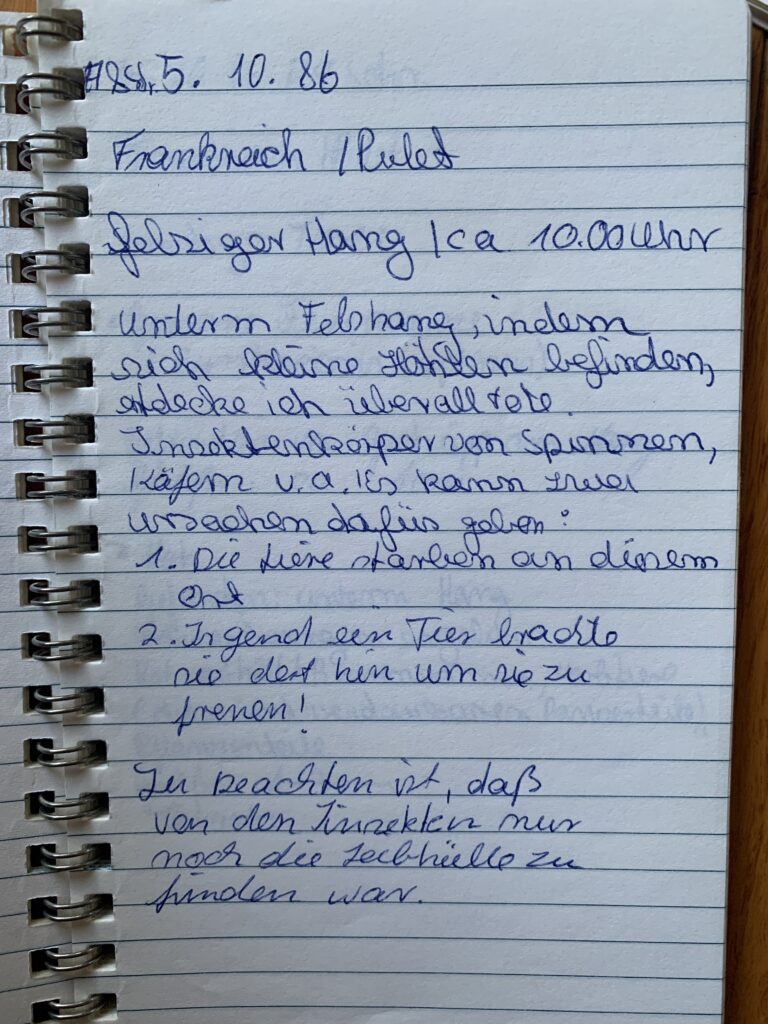

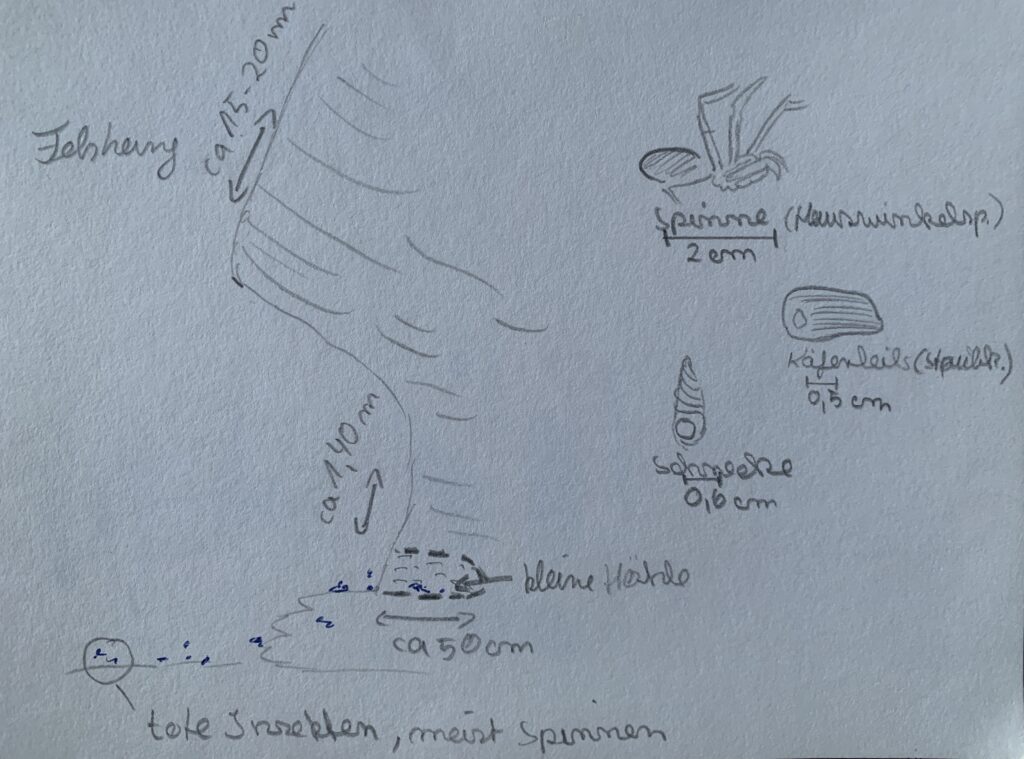

The back of our house became my own little research station. I had a Kosmos nature book that taught me how to set insect traps to study the species in our garden; how to pour plaster into animal footprints to cast the tracks of passing wildlife; how to count the types of snails eaten by blackbirds by finding the stones where they cracked open the shells; and how to dissect owl pellets to see what they had been hunting. I always carried a science journal to record my findings and illustrate them with drawings — keep in mind, this was still thirty years before smartphones and digital cameras were invented.

Above (first row): My treasured Kosmos nature book — the guide that taught me how to explore the wildlife in my own backyard. Above (second and third rows): Pages from my childhood science journals, filled with my very first observations and field notes.

Books, Documentaries, and Early Scientific Imagination

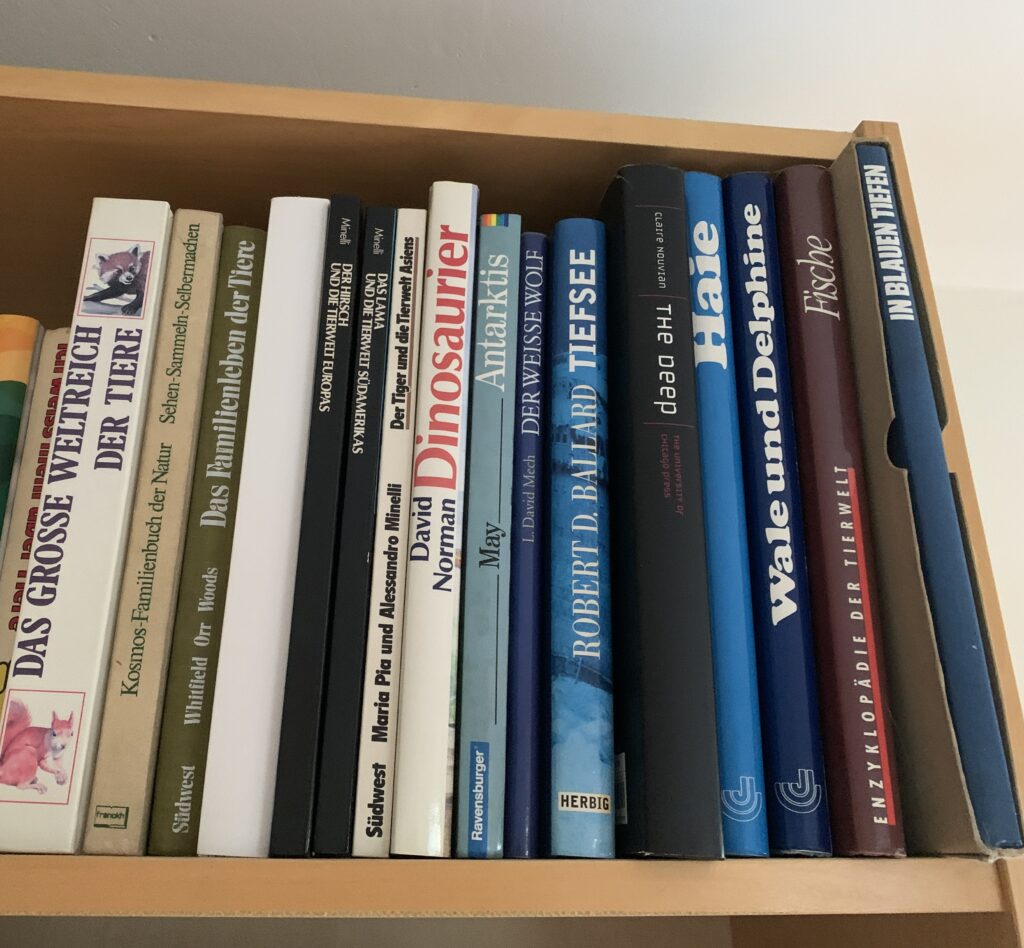

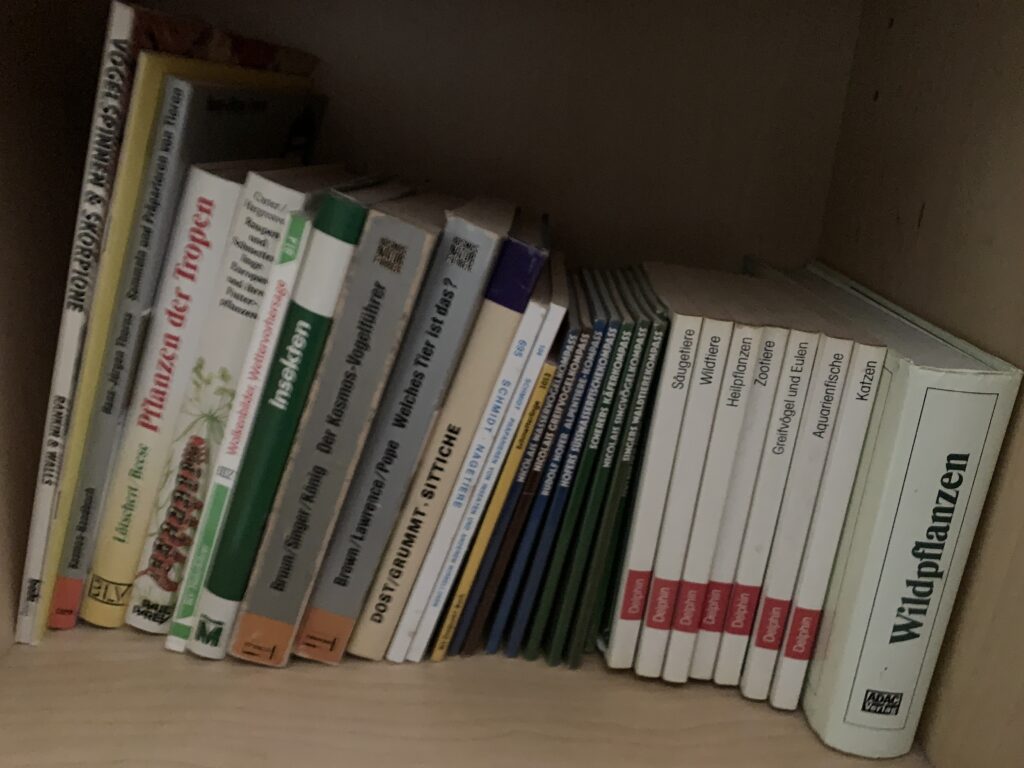

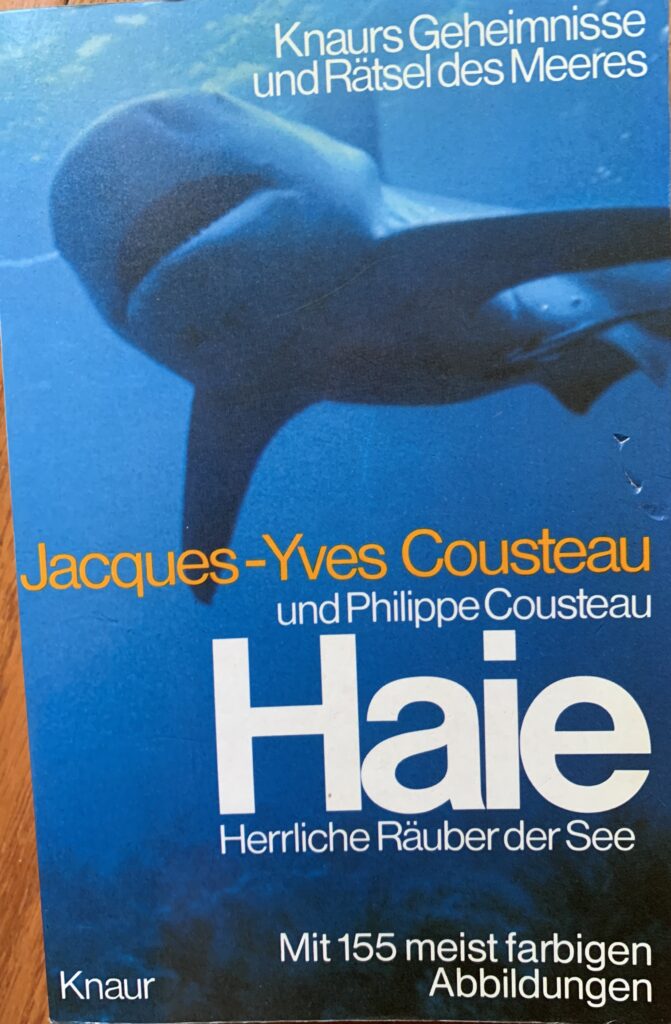

Science books became my obsession. I spent nearly all my pocket money on them, and for every birthday my relatives gave me one or more volumes of the Was ist Was? (“What Is What?”) series — a set of beautifully illustrated junior science books that explained everything from volcanoes, dinosaurs, and microbiology to oceans, technology, and outer space. Each volume focused on a single topic, filled with engaging illustrations, info boxes, and content that was easy to understand yet endlessly fascinating. I even created my own exams about what I had learned, studied for them, and then tested myself. Call me a nerd if you like.

Above: Some of the science books that fueled my curiosity and shaped my love for discovery as a child and teenager.

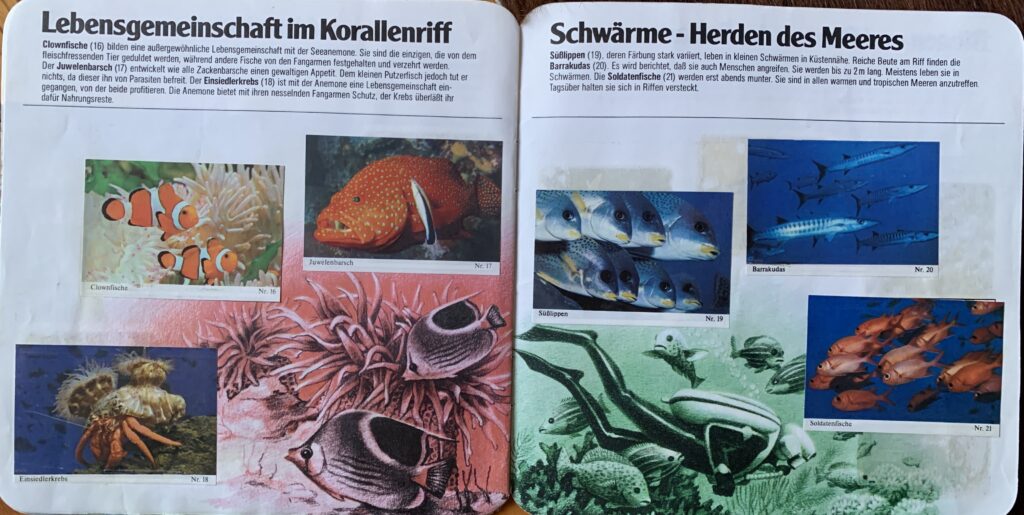

Beyond books, I was deeply inspired by nature documentaries on television. I grew up watching the Sunday afternoon films by Heinz Sielmann, the Grzimeks, and Jacques Cousteau — each one opening a new window into the natural world. Around the same time, I also collected animal stickers from Ferrero’s Hanuta and Duplo chocolate snacks and carefully added them to the corresponding collector albums. Over the years, the themes changed — one of my favorites was Marine Animals.

Above: One of my Ferrero (Duplo and Hanuta) sticker albums — a childhood collection that combined my love for animals and discovery. Fun fact: I would later use the Book for Seawater Analyses by Klaus Graßhoff, who signed the Ferrero album, in my laboratory.

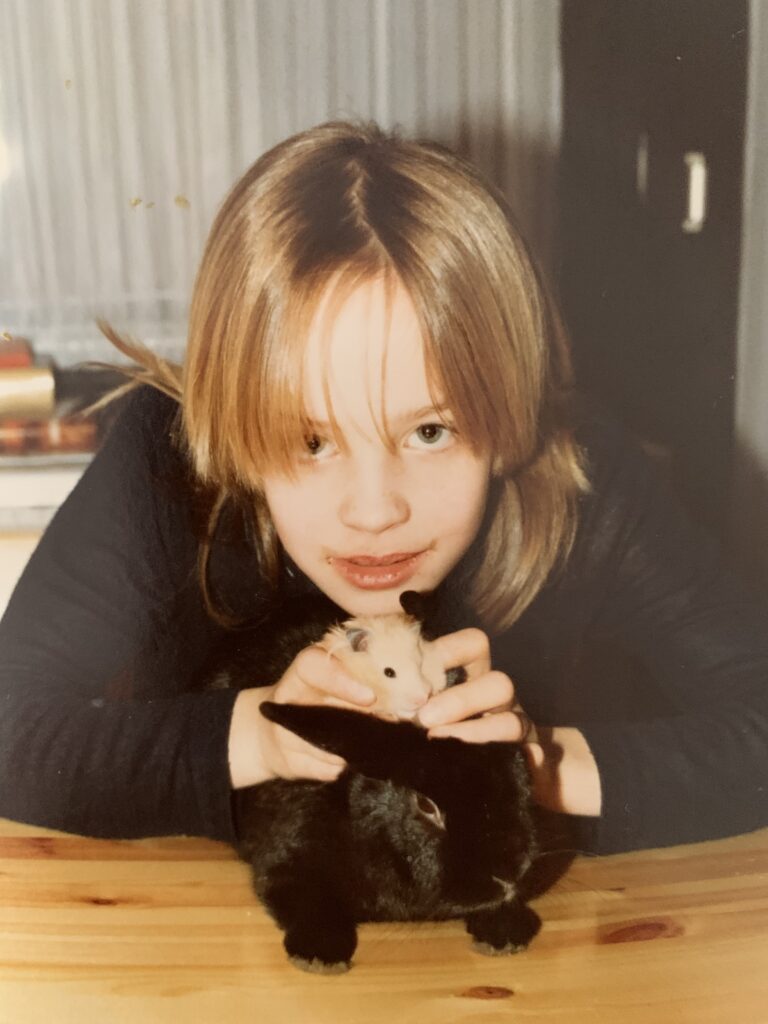

The Treude Zoo and My Early Anatomy Lessons

Another major influence on my love for nature — and especially for animals — was my parents’ generosity in allowing me to keep almost any pet that could be found in pet shops in the 1970s and 80s. My first pet was a tortoise when I was three years old. Over the years came turtles, goldfish, rabbits, guinea pigs, hamsters, gerbils, mice, chinchillas, all kinds of birds (canaries, budgies, zebra finches), and eventually a dog.

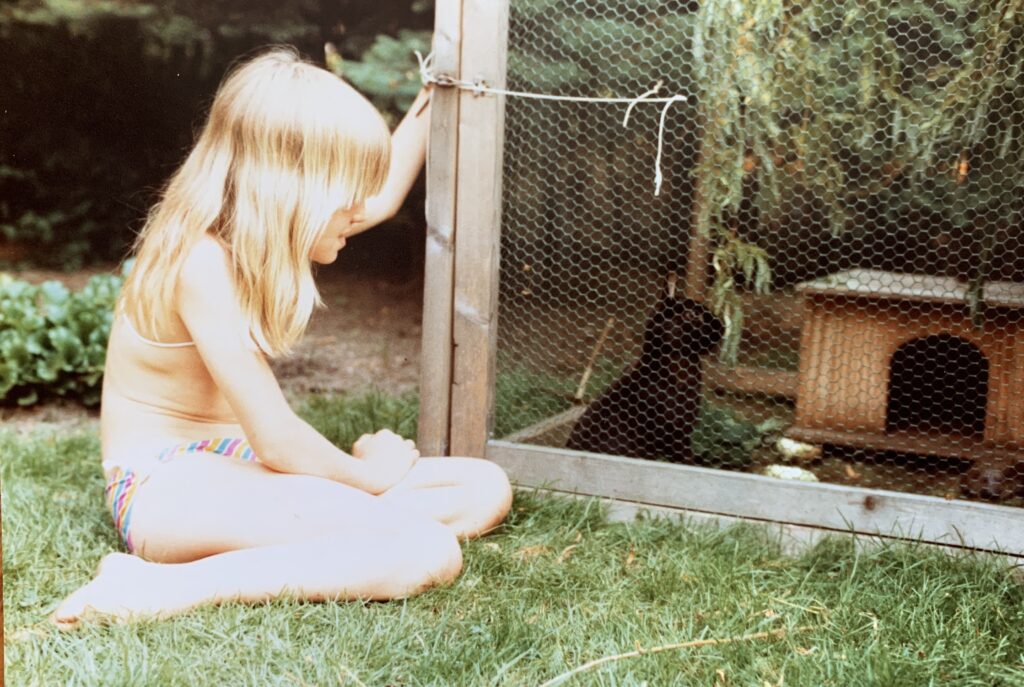

My father, who is skilled in joinery, built me a large wooden house with indoor cages and outdoor enclosures for my animals. I bred rabbits, chinchillas, and birds — and most of them stayed with us. We also fostered animals, mostly cats and once even a polecat, that needed temporary homes until they found new families.

The only condition my parents set for keeping all these animals was that I feed and clean them myself (except for our dog Esko, who quickly became a full family member). This taught me early on what it means to take responsibility. At one point, our local newspaper even wrote a short column about what they called the “Treude Zoo.”

Above: A few snapshots of me with my beloved pets — the furry friends who taught me to care and observe.

Given the large number of animals that lived — and eventually died — in our home, we had a small pet cemetery with a wooden cross in our garden. Sometimes, when I dug a hole to bury one animal, I accidentally unearthed another that had been resting there a bit longer. I tried to remember where the recently buried ones were, but over time I lost track of the older graves. When that happened, I examined the bones I found — and I even kept the shell of my beloved tortoise, which had been naturally cleaned of tissue after a few months underground. That experience sparked my fascination with animal anatomy.

Later, I put my large box of mealworms (originally meant as live food for my birds) to new use: they became my assistants for cleaning the skulls and bones of animals I found dead on the road or in the garden. Soon, I began rescuing the dead mice from our neighbor’s cat before it could swallow them, and dissected them in my little animal house in the garden. I sorted their organs — liver, heart, kidneys, and so on — into egg cartons and nailed the mouse skins to the wall.

I sometimes wonder if, in today’s world, that might have been the moment when parents would take their child to a psychiatrist and ask, “Is my kid okay?” But my parents were remarkably relaxed about my passion. They even proudly showed my study specimens to visiting friends. They understood that it was pure scientific curiosity driving me — and I never once harmed a living animal to satisfy it.

Above: My childhood room, already crowded with animal cages. Realizing we all needed more space, my parents built outdoor enclosures (bottom left) and later a proper animal house (bottom right) — a little paradise for my pets and me.

From Caring for Animals to Studying Them

My love for animals soon led me to many volunteer activities. When I was ten, I began helping after school at our local veterinarian’s office. I kept the eyes of anesthetized cats and dogs moist and helped to calm animals during their examinations. This was the same veterinarian who gave us foster animals — the cats and even the polecat — as he worked closely with the animal shelter in the neighboring town.

When I was twelve, I started volunteering at that shelter myself. In the afternoons, I took the dogs for walks to give them a break from their kennels. I was always happy when a dog was gone the next time I visited, knowing it had found a new home. Some of the older or more difficult dogs stayed for years, and they were especially excited when I arrived to take them out.

At fourteen, I completed a two-week school internship at the Hannover Zoo to explore a profession I was seriously considering. I worked in the hoofed-animal section, caring for deer, moose, elk, antelope, camels, musk oxen, goats, and donkeys. I learned how to prepare food, how to design suitable enclosures for different species, and how even seemingly harmless animals can become dangerous if they feel threatened or cornered. I gained deep respect for the work of zookeepers — their patience, intuition, and responsibility. But I also realized that I wanted something more: not only to care for animals, but to study them — to understand the natural world on a deeper, scientific level.

Above: Me at the Hannover Zoo during my student internship. Proof that every era has its own style — mine just happened to include that 80s haircut.

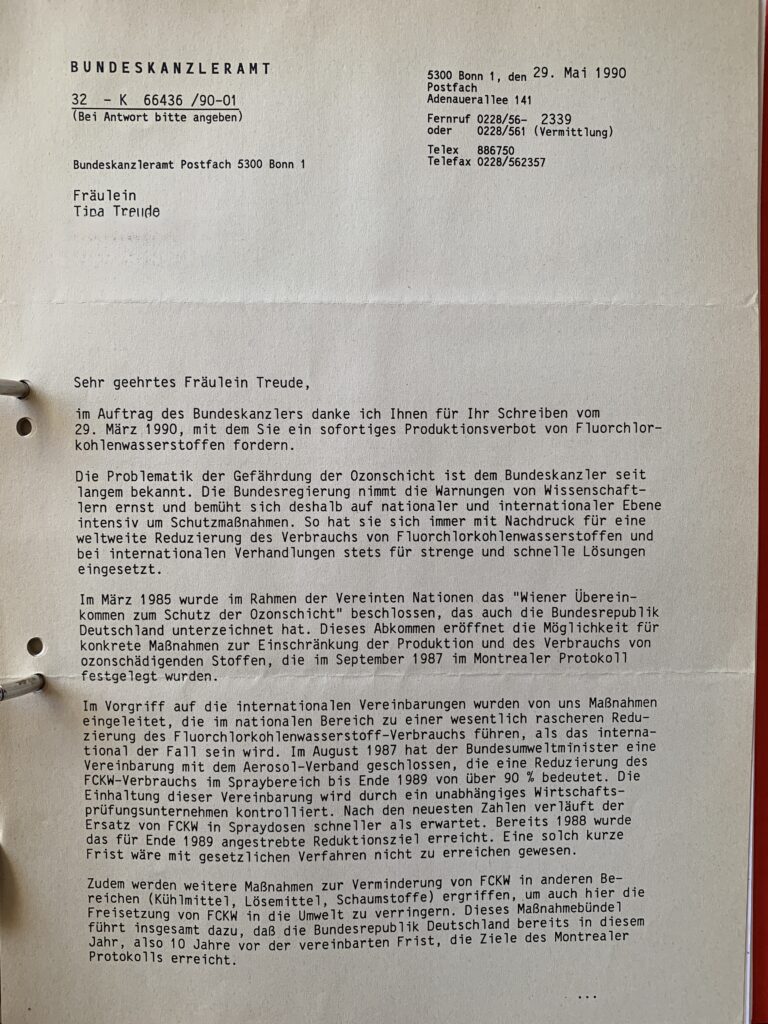

Teenage Activism and Environmental Awareness

When I entered puberty, I began to feel an urge to change the world and to rebel against what I saw as unfair. I became a passionate advocate for animal rights and environmental protection. I joined animal activists during protests and even once locked myself inside a giant chicken cage to demonstrate against cruelty in poultry farms. For about two years, I was a vegetarian — not because I disliked meat, but because it was easier to say “I don’t eat meat” than to explain that I only wanted to eat meat from animals that had lived a happy life.

Above: Me (center right) at a protest against animal hunting — and yes, it was the 1990s, complete with henna-red hair.

I wrote countless letters — this was still before email — to animal welfare and nature organizations, asking for more information about their campaigns. I also wrote to companies, politicians, and city administrations to complain about environmental issues. Together with a teenage friend from my neighborhood, I started collecting recyclables like aluminum, plastic bags, batteries, and egg cartons. We walked from house to house with a wheelbarrow, ringing doorbells and asking if people had anything to recycle. Month after month, more people began saving recyclables for us, and we proudly hauled them to the local collection sites — long before official recycling bins became common.

Above: Response letters from institutions and politicians I contacted as a teenager, hoping to make them aware of the environmental and animal welfare issues that mattered deeply to me.

Discovering Chemistry and the Science Behind Nature

I also became fascinated by chemical analysis, thanks to my childhood friend who, like me, developed an early interest in science — though his passion was chemistry. He’s now a toxicologist. While I was busy with animals and nature, he received a junior chemistry set with all sorts of reactions to explore. Together we started buying additional chemicals from our local pharmacy — something that would probably be impossible today, as we were far too young to be sold ingredients that could form gunpowder — just to learn how chemistry worked.

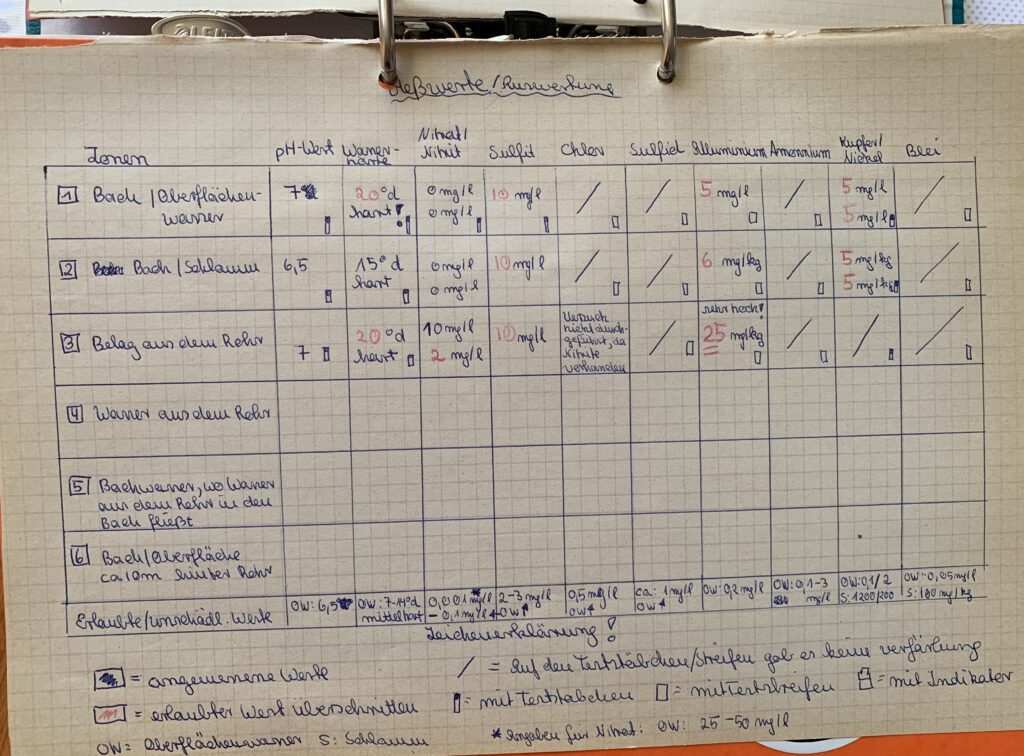

For my part, I became curious about how to test whether a lake or creek was healthy. I bought simple field kits to measure pH and nutrient levels. It was the era of acid rain and Waldsterben (forest dieback), the BASF chemical spill in the Rhine River, the Chernobyl disaster, the discovery of the ozone hole, and the growing awareness of ocean eutrophication caused by agricultural runoff. Much like the youth movements of today who fight for their future in the face of global warming, we were frightened and angry about how the adult world treated the environment. I felt an ever-stronger urge to understand natural systems — and how they respond to human impact.

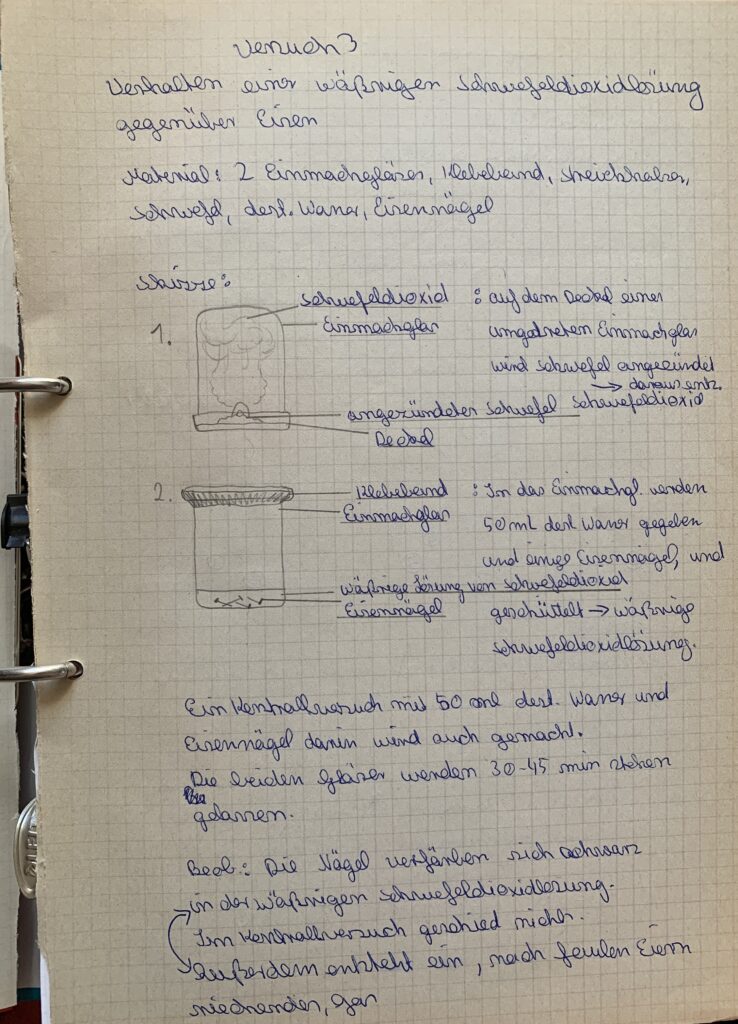

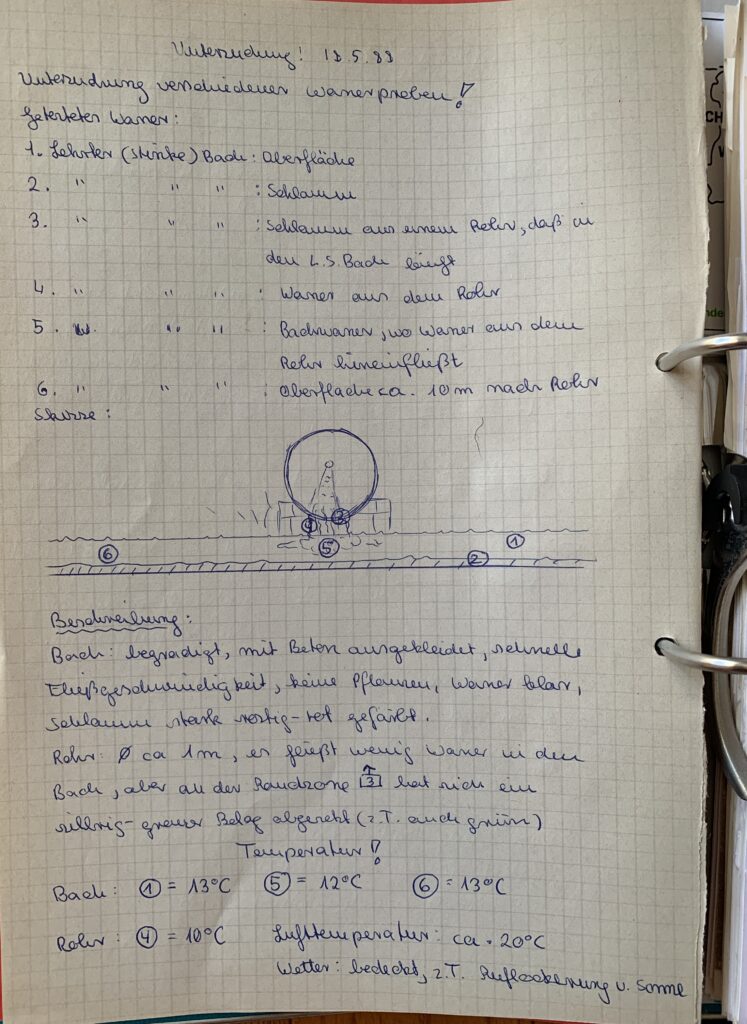

Above: Notes from my childhood science journals documenting chemical experiments and analyses of local aquatic systems.

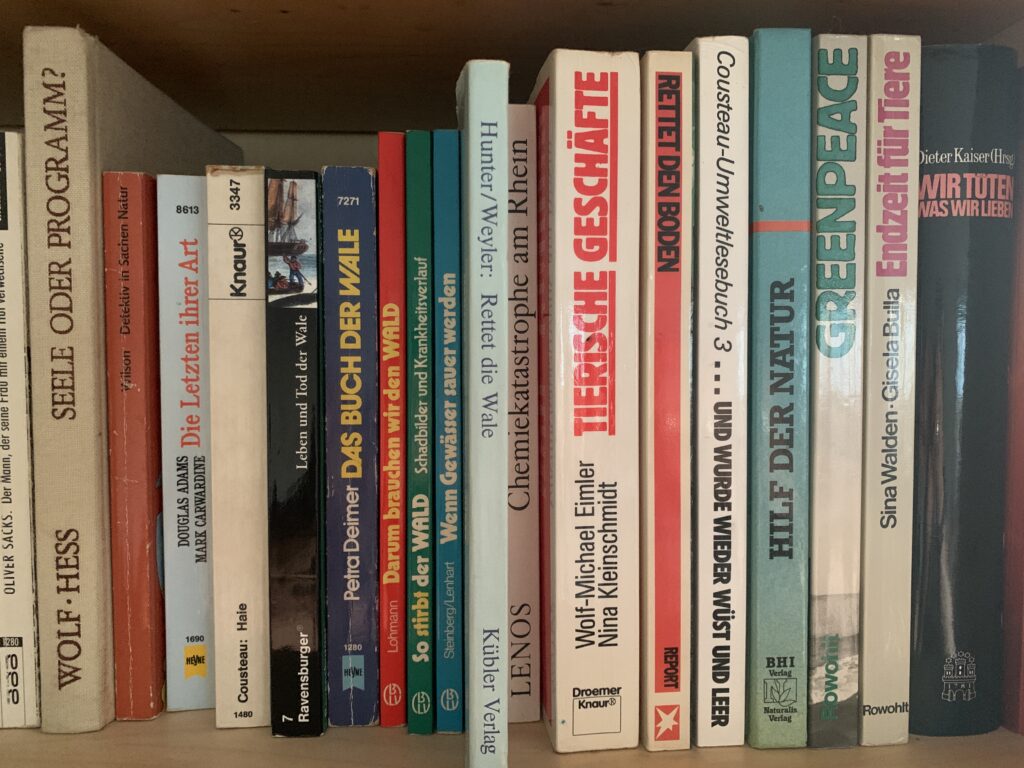

Above: A selection of the environmental and animal protection books that sparked my concern for nature and equipped me to speak up for it. And yes — there’s a book by Petra Deimer, one of my early idols (continue reading to learn more).

Falling in Love with the Ocean

But how did I finally become interested in the oceans, you might wonder. My first clear memory of the sea wasn’t exactly a good one. My childhood home was about two and a half hours from the coast, and one day my father decided to take me to the North Sea to show me the ocean. When we arrived, there was no ocean. It was low tide — the water was gone. My father told me it would take too long for it to return, so we drove back home. I was deeply disappointed, not realizing that I had just been staring at one of nature’s greatest wonders — the Wadden Sea — which is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In the end, three things sparked my true fascination with the ocean (and no, the low tide at the North Sea was not one of them):

Jaws, a seawater aquarium, and my first scuba dive.

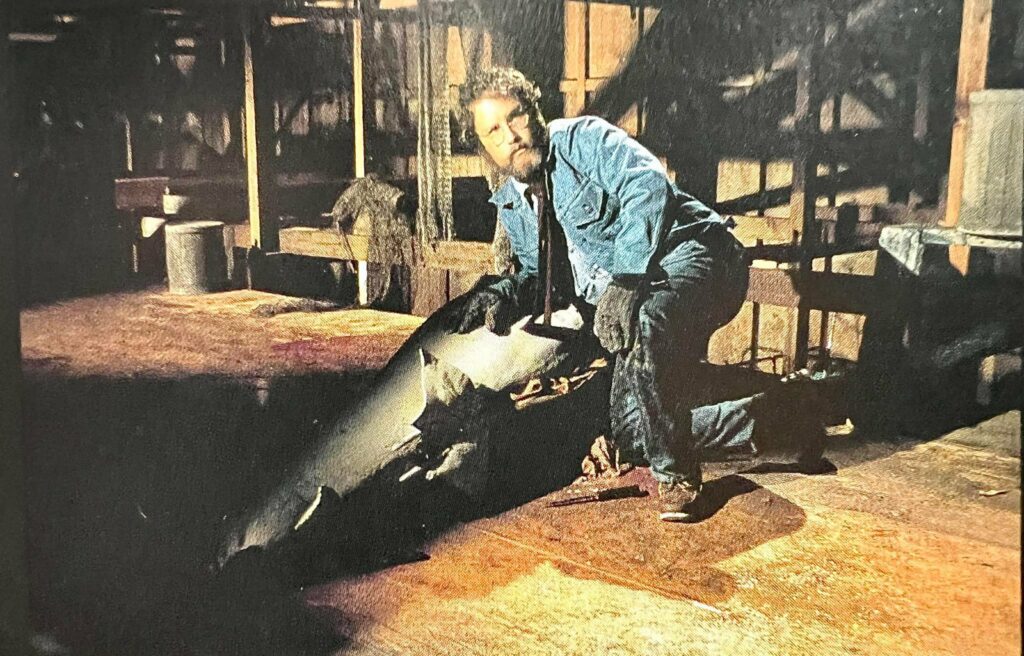

When I was eight, my parents bought a video recorder — a Video 2000 (yes, there was more than just VHS in those days). We recorded countless movies from television, and I had a habit of watching my favorites over and over again. One of them was Jaws. I loved — and still love — Jaws. I was completely captivated by the oceanographer Matt Hooper, played by Richard Dreyfuss. I wanted to become Matt Hooper.

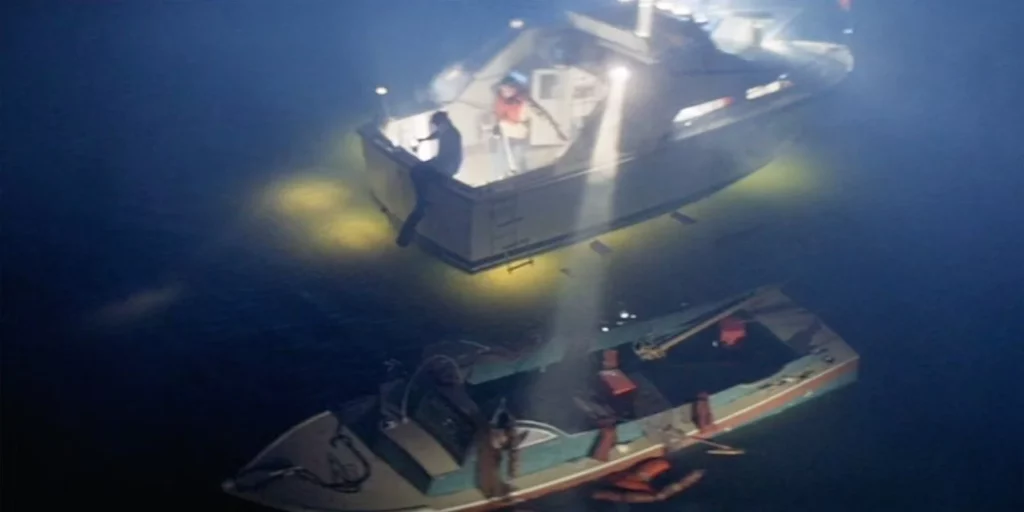

One of my favorite scenes is when Hooper dissects a shark and pulls out a license plate. Another one is the night scene when he dives to the small abandoned boat and finds The Head! This year (2025) marks the 50th anniversary of Jaws, and I now proudly own a Jaws purse, a POP! Hooper figure, and a squeezable Quint “stress beer can”. I know every scene and every line of dialogue by heart. Maybe thanks to Steven Spielberg, I decided to become who I am today — or at least, Jaws was an important spark that steered me toward ocean science.

Above: Scenes with Matt Hooper in Jaws — the shark dissection (left) and the tense night-dive preparation (right) that made ocean science look like the ultimate adventure. Images from Jaws (1975), © Universal Pictures. Used here for educational and illustrative purposes.

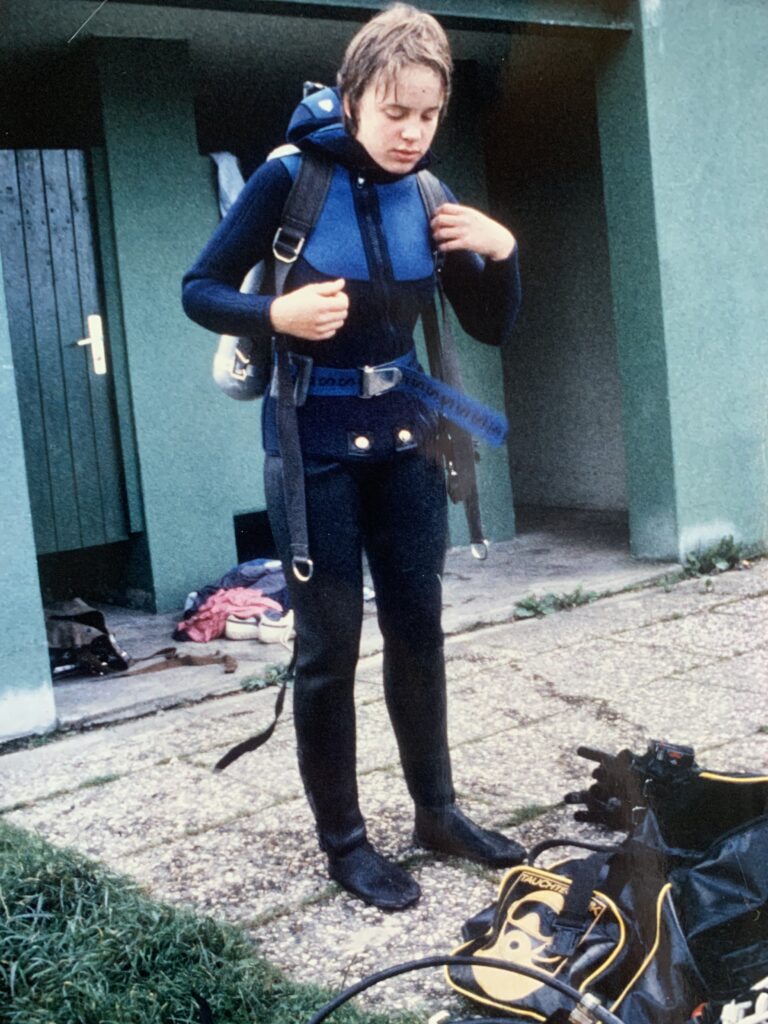

The other two big influences came from our neighbor, who owned a large and mesmerizing seawater aquarium, and who, when I was thirteen, stuffed me into a neoprene suit and taught me how to scuba dive. In those moments, I felt just like Hooper — except that our local lakes had no great white sharks, only large pikes. It would take several more years, and many lake dives, before I finally dove into the open ocean. But that was all it took to get me hooked.

Above: Returning from my first dive (top left) in a local lake known for its large pikes (top right). My neighbor’s seawater aquarium — a mesmerizing window into marine life that I loved to observe (bottom).

Choosing the Path of Ocean Science

Once I had decided that I wanted to become a biological oceanographer, I was on a mission. I began to plan my career carefully. I wrote letters to my idols — among them Petra Deimer, a marine biologist and conservationist — asking for advice on how to follow in their footsteps. Encouraged by Petra Deimer, I even went to the job center in Hannover to find out exactly what I needed to study to reach my goal.

Above: The response I received from Petra Deimer after asking how to become a marine biologist. I was beyond excited to get her letter — it showed me that career paths in science don’t have to be straight or predictable. Although she warned that becoming a marine biologist is not an easy journey, I wasn’t discouraged; instead, I did even more homework to find my own path.

When the time came to choose my major subjects for the German Abitur, I selected them strategically: Biology, Chemistry, Earth Science, and Latin. Funnily enough, the first three already made me a kind of “bio-geo-chemist.”

When I began my studies at the University of Hannover, I enrolled in general biology, which included zoology, botany, chemistry, and physics. After completing my Vordiplom (roughly equivalent to a bachelor’s degree), I transferred to Kiel University, where I began my studies in Biological Oceanography — and, as they say, the rest is history.

From Zoology to Geomicrobiology

But wait — there is still one story to tell: the story of how I became a geomicrobiologist rather than a zoologist.

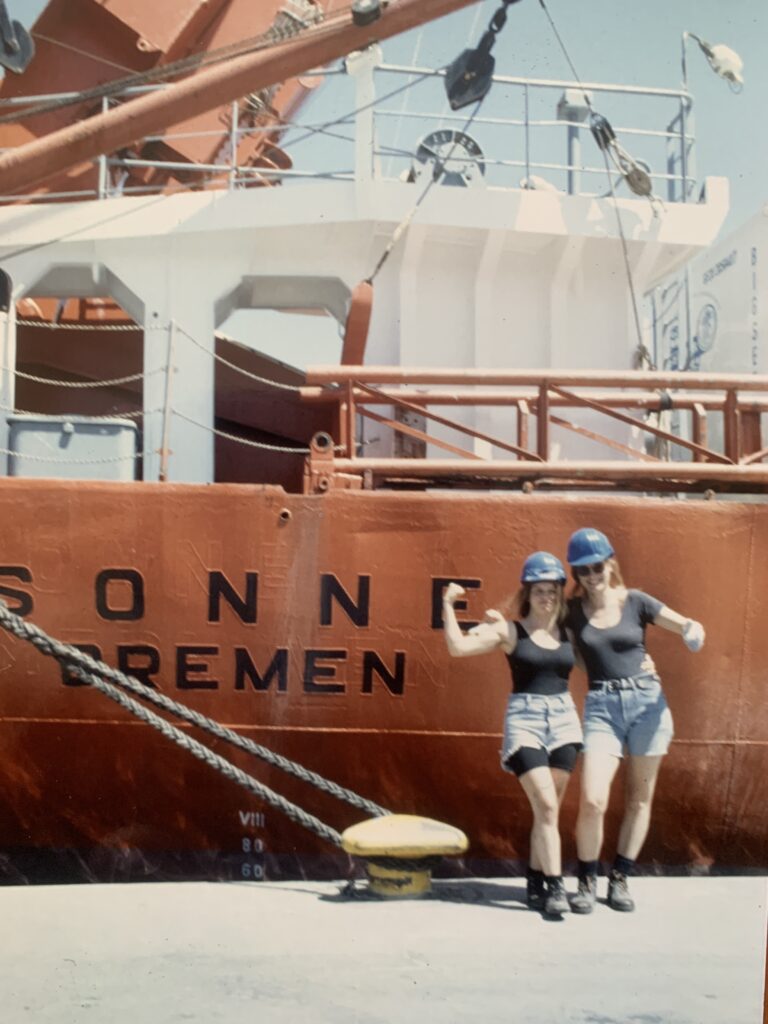

While studying at Kiel University, I had the privilege of joining several multi-week research expeditions aboard the German research vessels Meteor, Polarstern, and Sonne as an undergraduate research associate. During one Sonne cruise to the deep Arabian Sea, I collected samples for my diploma thesis, which focused on deep-sea scavengers such as Munidopsis crabs, amphipods, grenadier and zoarcid fish. Together with a long-time study friend, I deployed lander-based traps on the seafloor to capture these animals. At that time, my attention was still fully on zoology.

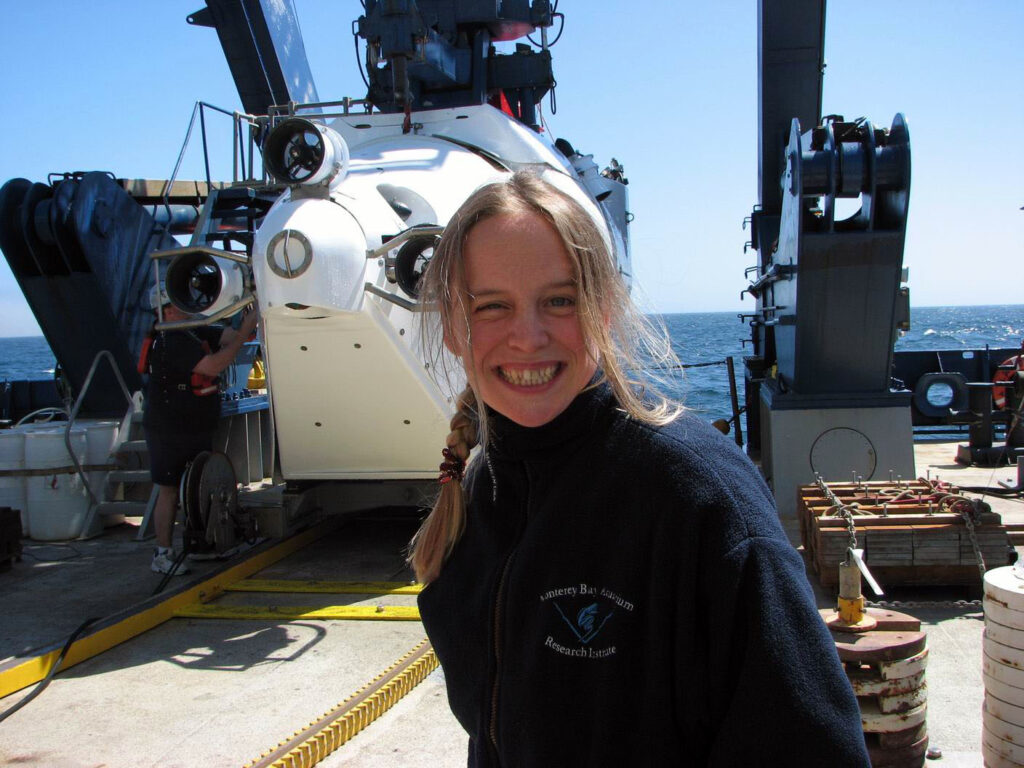

Above: Me (left) and the technician I worked for, proudly posing in front of the research vessel Sonne — my first taste of life at sea as an undergraduate research associate.

That changed just before I officially graduated. On what would be my final expedition as an undergraduate, I again joined the Sonne — this time off the coast of Oregon, where GEOMAR scientists were studying gas hydrates at a seafloor formation called Hydrate Ridge. It was there that I became fascinated by the hidden power of microorganisms. It was also on that expedition that my future PhD advisor, Antje Boetius, collected samples for her now-famous Nature paper describing the organisms responsible for the anaerobic oxidation of methane.

Never would I have imagined, as a child fascinated by animals, that I would one day work with microorganisms. But this expedition revealed to me how microbes can transform entire environments — feeding on methane and supporting diverse chemosynthetic communities. Since then, I’ve immersed myself in many microbe-related topics, exploring the remarkable processes these tiny organisms perform and how they shape our planet.

Yes, I sometimes miss working with animals, but in the end, everything in nature is connected. I take great joy in collaborating with zoologists who study symbioses and other interactions between animals and microbes — where my two worlds meet.

Gratitude and Reflection

Did I ever regret my decision to become an ocean scientist, you might wonder? The answer is no — never! I think it was always part of me: the curiosity to study the natural world, my connection to animals and nature, my love for the ocean (despite my first low-tide experience at the North Sea), and the sense of adventure that comes with exploration.

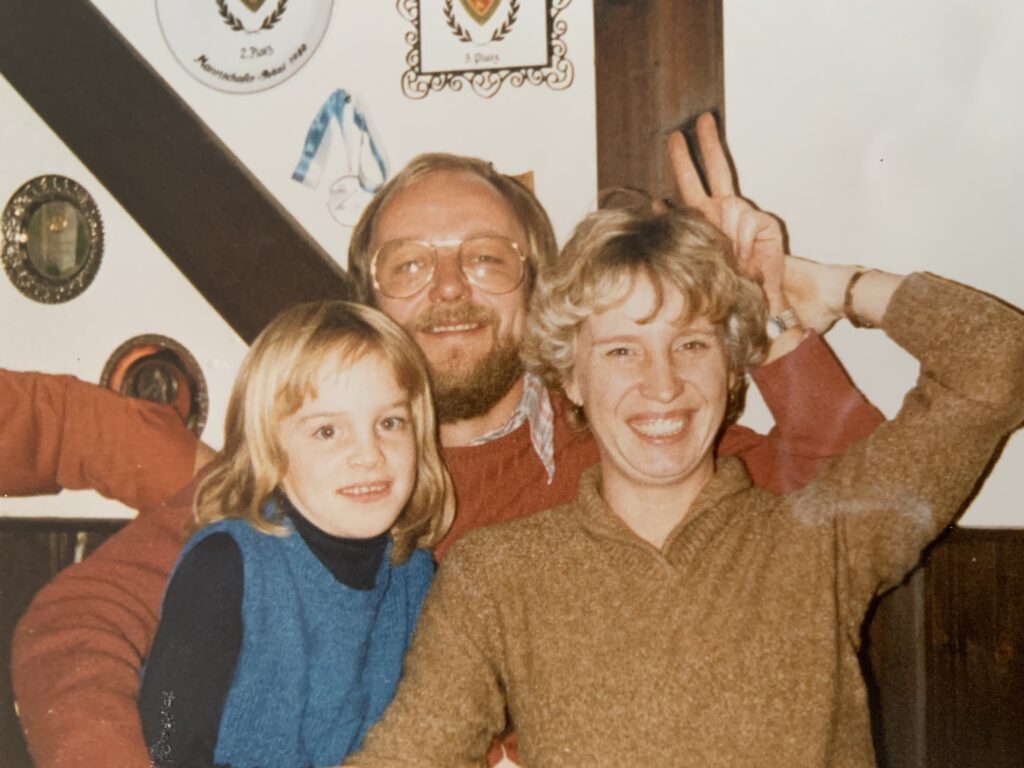

But I would probably never have pursued these goals without the support of my parents — and I don’t mean just financial support. In Germany, education is essentially free, or at least far more affordable than in the U.S. Of course, my parents helped me financially where needed, but what I am endlessly thankful for is their belief in my dreams and their encouragement of my interests. They always told me they would support me no matter what I chose to become — as long as I loved what I was doing. So that’s what I did. And I always knew I had their full backing.

Thank you, Mom and Dad!

I also want to thank my husband, whose steady support has carried me through the years — and who patiently endures my long absences while I’m out exploring the oceans or attending scientific meetings. Every now and then, I manage to pull him into my science world a bit, especially when there’s an outreach event or nature adventure he can’t escape from.

Love You, Steffen!

A Note to Future Scientists

Do I have any advice for future scientists? If you’re reading this because you’re looking for guidance on how to become one, my advice is simple: listen to your heart. It doesn’t matter at what stage you discover your love for science — as a child, a teenager, or later in college. What matters is that you are passionate about it.

Throughout my life, curiosity has driven me to understand how nature works and to continue along the path toward becoming a scientist and, ultimately, a professor. I never said, “I want a PhD,” or “I want to be a professor.” I simply wanted to explore and discover nature. The PhD and professorship were just the natural frameworks that allowed me to keep pursuing that passion.

But be warned: academia demands passion. It is not a nine-to-five job. Some people say, “Science is a cruel mistress,” because passion often drives you to work harder and longer than you are paid for. You need strong self-motivation to persist — to write proposals, publish findings, and navigate rejection and uncertainty. There is no boss telling you what to do each day; you must generate your own ideas and turn them into projects.

This is where passion and curiosity become your true engines — powerful forces that keep you moving forward, and they cost nothing. I believe the best scientists are those driven by this inner energy. Anyone who shares that drive can become a scientist, no matter where they come from: whether or not their parents were academics, regardless of wealth, school background, or birthplace (though, of course, good grades help). In the end, what matters most is that spark of curiosity and the determination to follow it.

Tina Treude

PS: Stay tuned! I’m still unearthing old photos, letters, and memories — and I’ll continue updating this page as new discoveries surface.