End of June 2023, our group set ‘sail’ to participate in two back-to-back marine research expeditions onboard the research vessel Atlantis (AT50_11 and _12), which hosts the famous deep-sea submersible Alvin. The total length of the two expeditions, which were supported by the National Science Foundation and organized by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, was over 5 weeks and took us to two different types of marine environments off the coast of southern California.

The first expedition (AT50_11) focused on microbial processes in the oxygen minimum zone of the Santa Barbara Basin. High productivity of plankton in the surface water and weak ventilation of the deep basin water triggers a strong decline of oxygen when bacteria feed on decaying planktonic biomass. The degradation of the organic material at the seafloor initiates a complex set of microbial and chemical processes, including the development of massive sulfur bacteria mats, which feed on hydrogen sulfide produced in the sediment. While most of these processes are natural, we are also interested to understand potential intensification and alteration of the processes related to human impacts such as climate change. For our research, we descended to the seafloor (maximum depth around 590 m) with the submersible Alvin for the deployment of chambers to measure fluxes of chemicals (such as oxygen, nitrate, sulfide) into and out of the sediment. Further analytical support was provided by the cute autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry, which completed several pre-programmed dives through the Santa Barbara Basin without a pilot to measure oxygen distribution and to monitor seafloor coverage of the sulfur bacteria mats. This NSF-funded expedition was a collaboration with the UC Santa Barbara (Dr. David Valentine), the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany (Dr. Felix Janssen), and the Mt. San Antonio College (Dr. Tania Anders)

The second expedition (AT50_12) aimed at cold seeps that release fossil methane from the seafloor. Cold seeps are found at many locations off the coast of southern California (Malibu, Santa Monica, Redondo Beach, Palos Verdes, San Pedro, Del Mar) and seepage is often facilitated through migration of methane along tectonic fault systems. The methane serves as an energy and carbon source for many organisms and creates special cold seep communities. The seep ecosystem usually starts with microbes, who feed on the methane and provide biomass for other organisms higher up in the food chain. The overall aim of the project was to understand the connectivity between methane and organisms and the importance of cold seeps for the overall health of the deep-sea ecosystem. On our dives to the up to 1000 m deep methane seeps, we collected seep rocks (carbonates made from methane-derived carbon) and sediments to study methane-eating microbes and animals associated with this ecosystem. This NSF-funded expedition was a collaboration with the Scripps Institute of Oceanography (Dr. Lisa Levin), the Occidental College (Dr. Shana Goffredi) and Caltech (Dr. Victoria Orphan).

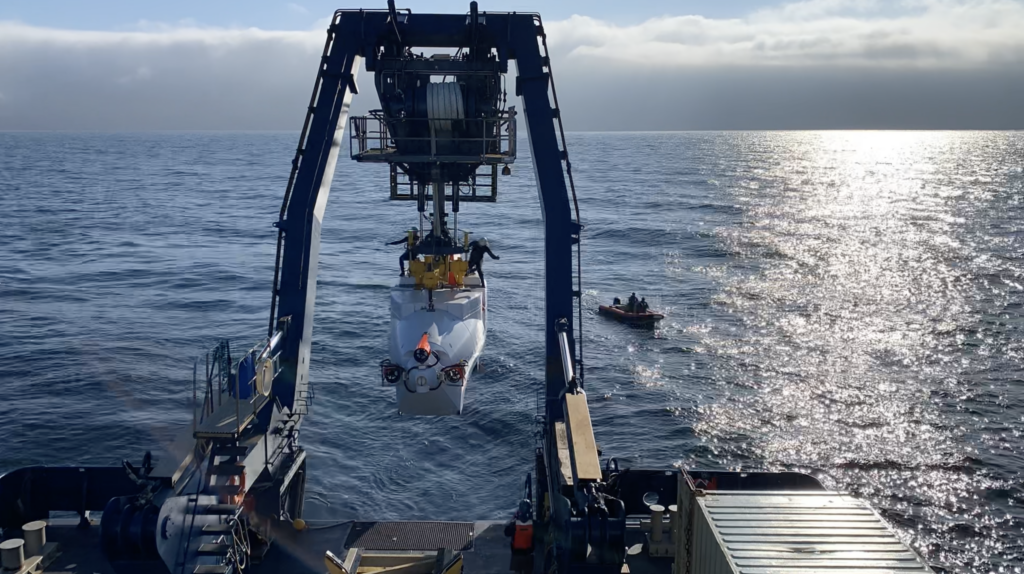

Diving with a deep-sea submersible such as Alvin is a dream come true for many marine scientists. It is not unlike boarding a spaceship – only few people in the world get a chance to experience it. Before boarding the submersible, scientists receive a safety training and must obey several safety rules, such as only wearing flame-resistant clothes and leaving any non-tested electronics such as cellphones behind. All Alvin pilots are Navy-trained and the solid titan sphere that holds the humans is approved for dives up to 6,500 m (21,325 feet). Once on board (usually two scientists and one pilot), everyone gets busy quickly to make sure samples requested are taken and documented with video cameras. The usual 6-8 hours in the sub fly by quickly. For the hungry ones, lunch boxes with sandwiches and chocolate are provided – so is a ‘toilet’ in the form of a plastic bottle. If people get asked what their most memorable moment in the submersible was, many mention the bioluminescence (glow) of organisms in the darkness of the deep sea. Once returned to the surface, those who experienced their first Alvin dive are welcomed back by the science crew with a bucket of ice-cold water, a joyful ceremony known as the ‘Alvin baptism’.

Next year, in late spring 2024, our group will get closer to Alvin’s dive limit when we will explore methane seeps off Kodiak Island (Alaska) at depths up to 5,500 m. Data gained during this future expedition will be compared to data from the shallower southern Californian seeps to study shifts in the relevance of methane for the ecosystems relative to water depth.

Watch also the ‘Women of the Deep’ video produced by Lisa Levin’s group on YouTube.