Windows Viewpoint

Windows Viewpoint

Look around the Windows area of Arches National Park in Utah!

This video shows an impeccable view of Turret Arch, on the left, and the North & South Windows, on the right.

These formations are prime locations for the deep wonder that Arches National Park inspires!

How did all these formations occur? Why are so many located in this area of Utah?

In Arches there are over 2,000 natural arches. This number, always in flux. New arches are regularly formed and discovered, in fact, if you discover one you get to name it! Arches also founder, dust to dust.

“It was already curving gracefully when the Egyptian pyramids were still under construction. It stood defiantly while the mighty Roman Empire was collapsing an ocean away. It was still holding strong when the Declaration of Independence was being signed in 1776.”, wistfully written by the National Park Service when Wall Arch collapsed in 2004.

One day all the arches will be gone, indeed, but how did they form in the first place?

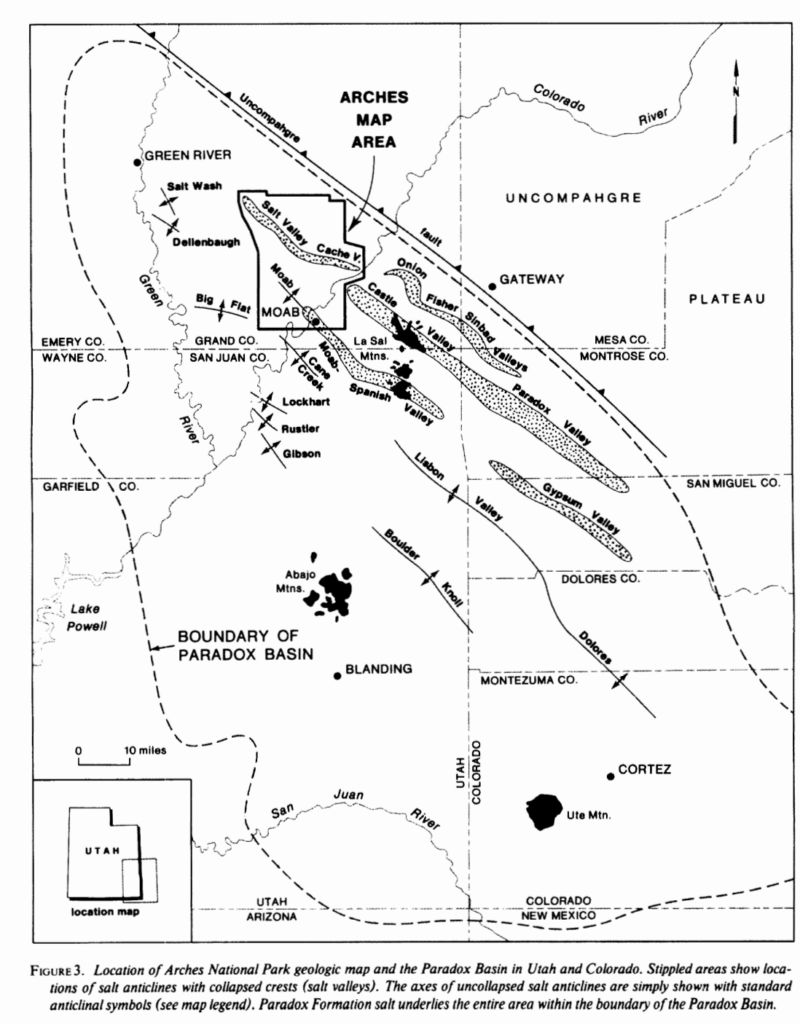

Beginning in the late Paleozoic, Utah was a shallow marine environment. Over the following 15 million years, sea levels rose and fell, trangressed and regressed, a whopping 29 times. All the while salt was being depositing in Paradox Basin which contains Arches National Park.

photo: (Doelling,1985)

Halite, and other evaporites, specifically gypsum and anhydrite, accumulated over this time forming vast salt beds. The water eventually completely evaporated out of the basin leaving a 14,000 foott (R.J Hite, 1968) thick floor of salt.

The evaporite deposit in Paradox Basin was buried beneath sediment for the next 300 million years. The overlying sediment homogeneously cemented into rock layers, most prominently in the Entrada and Navajo Sandstone formations which are found in Arches.

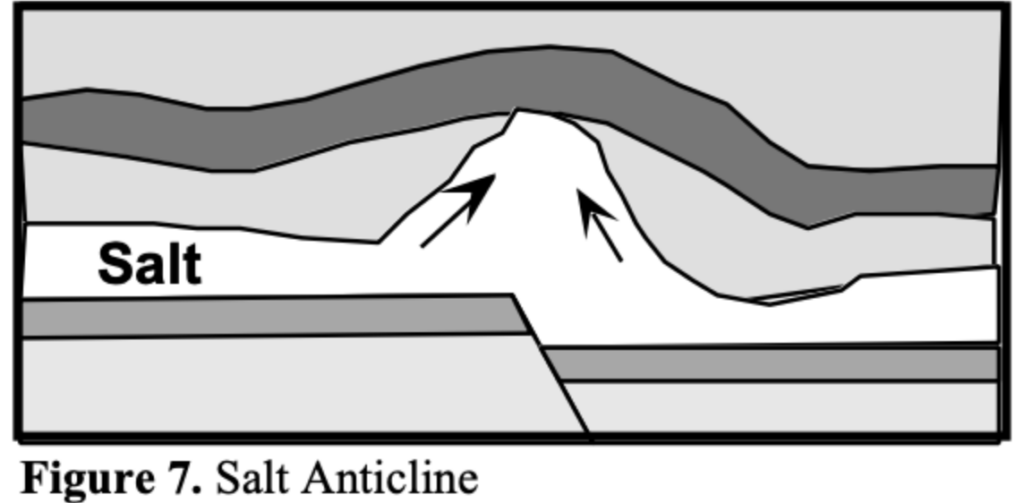

Because salt has low density and high ductility it flows under pressure. At a greater burial depths and higher temperatures, salt deposits becomes less dense than overlying strata. The higher temperatures at depth cause the salt to heat and expand, further increasing its buoyancy.

In Arches, the underlying salt was more buoyant than the sediment it had been buried beneath so it rose to the surface forming a salt dissolution feature called a salt diapir or salt dome. The salt dome formed an anticline which deformed the overlying strata by cracking the sandstone cap rock, creating parallel, vertical fractures called joints in the sandstone.

Photo: US Parks

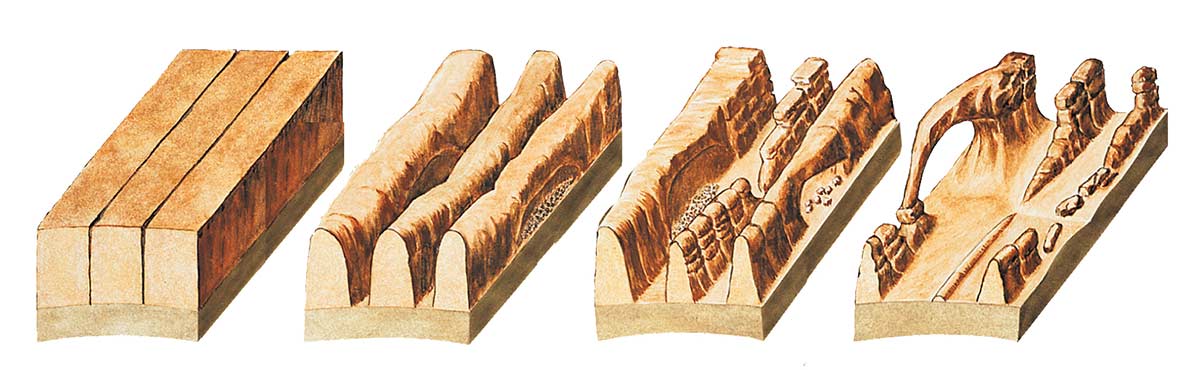

As the youngest layers on top of the salt and cap rock eventually eroded away, the jointed sandstone became exposed at the surface. This subjected the sandstone to the elements!

The open spaces where the rock was cracked open allowed water to flow in, which dissolved away the salt that has been exposed beneath the sandstone. Eventually the dome became depleted of the evaporites and collapsed to create a valley. Thin sandstone rock walls called fins, named for looking like fish fins, are the remnants of this process. The space between each fin ever widens as the sandstone erodes over time.

Explore the area on the map, it looks truly amazing in aerial view.

Water and wind are the main actors in arch formation.

Wind travels relatively uninhibitedly throughout this desert landscape, as there are not large trees or obstructions to slow it down. It essentially acts as a sand blaster that can whip with reckless abandon on the fins. This is an aeolian process known as abrasion.

Roughly 9 inches of rain fall annually in the area. The slightly acidic rain water combines with carbon dioxide in the air creating carbonic acid. This erodes the fins by dissolving the cement, calcium carbonate, that hold the grains together. This is chemical weathering process known as chemical dissolution.

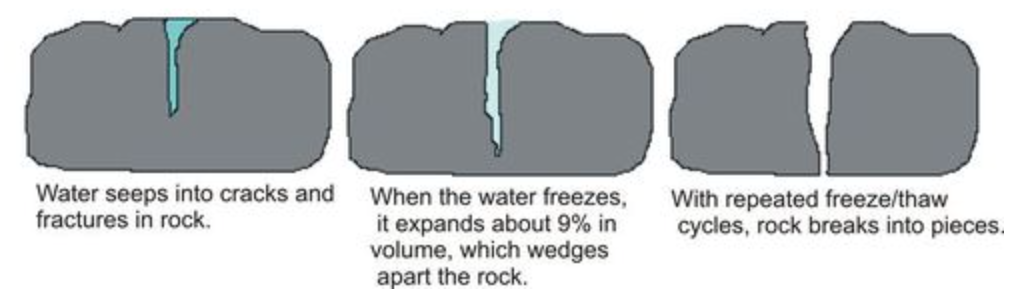

In the winter months water seeps into small cracks in the fins and freezes into ice. The expansion of the water as it freezes acts as a wedge that opens the rock, further cracking it open. This is a physical weathering process called “ice-wedging”.

Temperatures in the park can oscillate between freezing and melting in the span of one day during the cold season. Ice, Ice Baby! This process is constantly reworking the landscape.

This makes the snow in the video wonderfully interesting , evidence of the perpetuation of the natural processes annually present.

IIn some fins, the exposed layer of weaker rock lays beneath a stronger layer. The weaker rock will weather first and undercut the more resistant layer above it. This opens a hole. The top of the hole is the weakest part because it is heavy and unsupported. Gravity causes fractures and breaks off pieces. This process opens the holes into windows and windows into eventual arches.

Like seen in our 360 video, North and South Windows are younger than Turret Arch, but will eventually take the same shape as erosional processes continue. North,South Windows, Turret Arch, and Delicate Arch are considered ‘Freestanding Arches’, as they are not part of another rock wall, fin, or cliff.

Turret Arch is a freestanding arch named for being part of a castle-looking rock formation. It is the Tony Soprano of Arches. Notice the spire in the video. The pareidolia of a fortress isn’t hard to imagine. Erosion through weak parts of sandstone fins composed of Jurassic-aged Dewey Bridge Member of the Carmel Formation and Slick Rock Member of the Entrada Sandstone formed the archway, according to the Utah Geological Survey.

There are a few key reasons we see so many stone arches here.

- Very few Earthquakes in the area, allow the delicate arches to remain undisturbed seismically

- The goldilocks amount of rainfall allows slow sculpting of the arches.

- Humans are alive at the right time to behold them. They weren’t always here & won’t always be present.

As we understand how lucky we are to see these wonders, it motivates us to learn as much as we can about them, and leaves us with the impression of the artistry Earth employs. Millions of years culminated into something spectacular.